Your cart is currently empty!

Exploring America’s Foundational Documents

As we approach the 250th anniversary of American independence in 2026, it’s essential to delve into the historical and legal foundations that have shaped the United States. The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are not just historical artifacts; they are living documents that continue to influence governance and individual freedoms. This survey note provides a comprehensive analysis of each, drawing from extensive research to ensure accuracy and depth, aligning with the mission of freedom250.net to celebrate this milestone.

Historical Context and Significance

The journey to American independence began with colonial tensions and evolved through a war that forged a new nation. These documents, created between 1776 and 1791, form the backbone of American democracy, reflecting ideals of liberty, equality, and self-governance. As we look forward to 2026, their legacy is evident in American identity and global influence, with freedom250.net offering keepsakes like wood golf tees and coffee mugs to honor this history.

Declaration of Independence: The Birth of a Nation

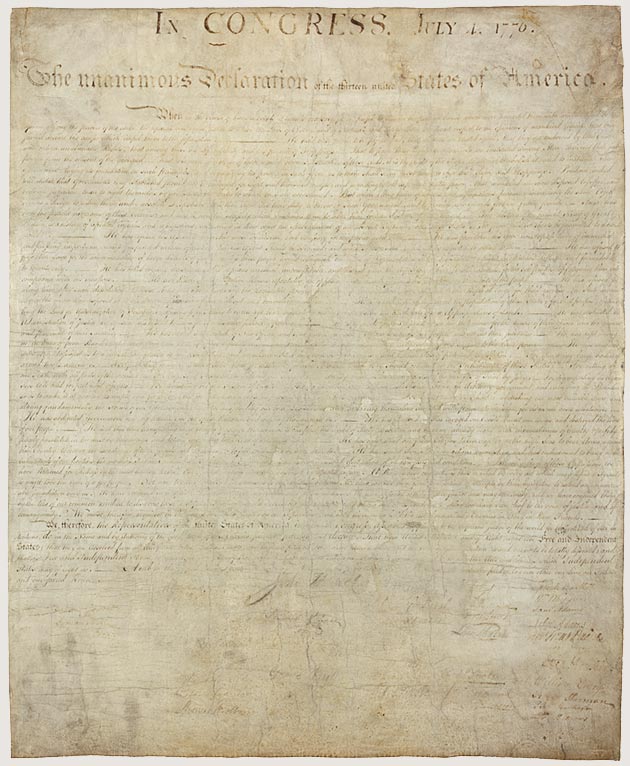

The Declaration of Independence is America’s founding document, marking the colonies’ separation from Great Britain. It outlines the principles that the government and American identity are based on, famously stating “all men are created equal” and that “legitimate government emanates from the consent of the governed.” It also lists reasons for the break, including grievances against King George III, justifying the Revolutionary War.

What It Is: Research suggests it’s the official statement declaring independence, embodying ideals that inspired global freedom movements.

When Written: The Second Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, 1776, and adopted Lee’s Resolution for independence the next day. Thomas Jefferson drafted the initial version, with corrections by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin on July 3 and July 4. Congress revised about one-fifth of the text, but the Preamble and basic document remained in Jefferson’s words.

Why Written: Inspired by colonial resistance, it was written to justify the break with Great Britain and seek foreign support for the Revolutionary War, particularly from France.

When Approved: Officially adopted on July 4, 1776, a date now celebrated as Independence Day.

Author: Thomas Jefferson, with the Committee of Five, including Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston.

Where Written: Jefferson wrote the first draft at his Philadelphia residence, 700 Market Street, second floor.

When Signed: Most historians agree that the Declaration was signed by the 56 members of the Second Continental Congress on August 2, 1776, although some delegates signed later.

Where Now: It is housed at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., also called the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom. The original document, faded from years of display, is maintained under archival conditions, symbolizing its enduring power. Abraham Lincoln called it “a rebuke and a stumbling-block to tyranny and oppression,” underscoring its global influence (National Archives: Declaration of Independence)

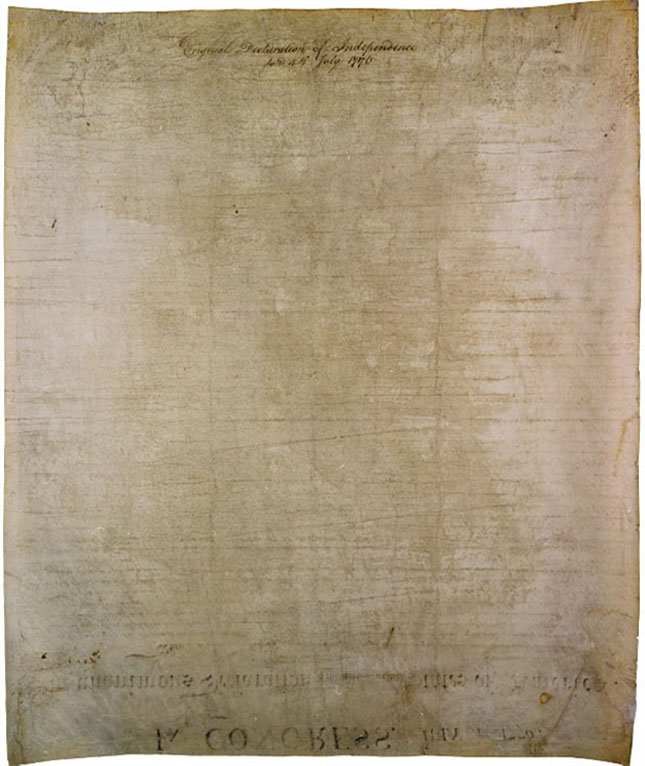

An unexpected detail is the inscription on the back, “Original Declaration of Independence dated 4th. July 1776,” noted during its preservation, adding a layer of historical intrigue.

U.S. Constitution: The Framework of Governance

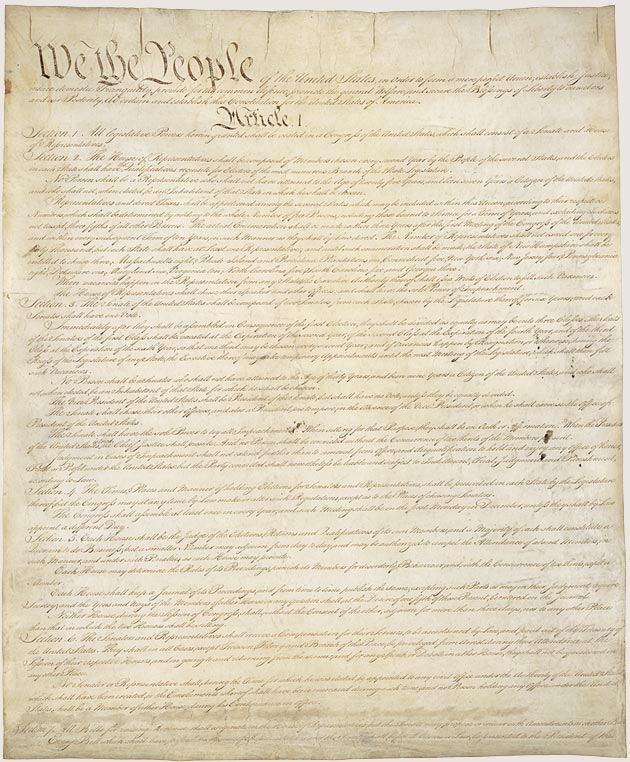

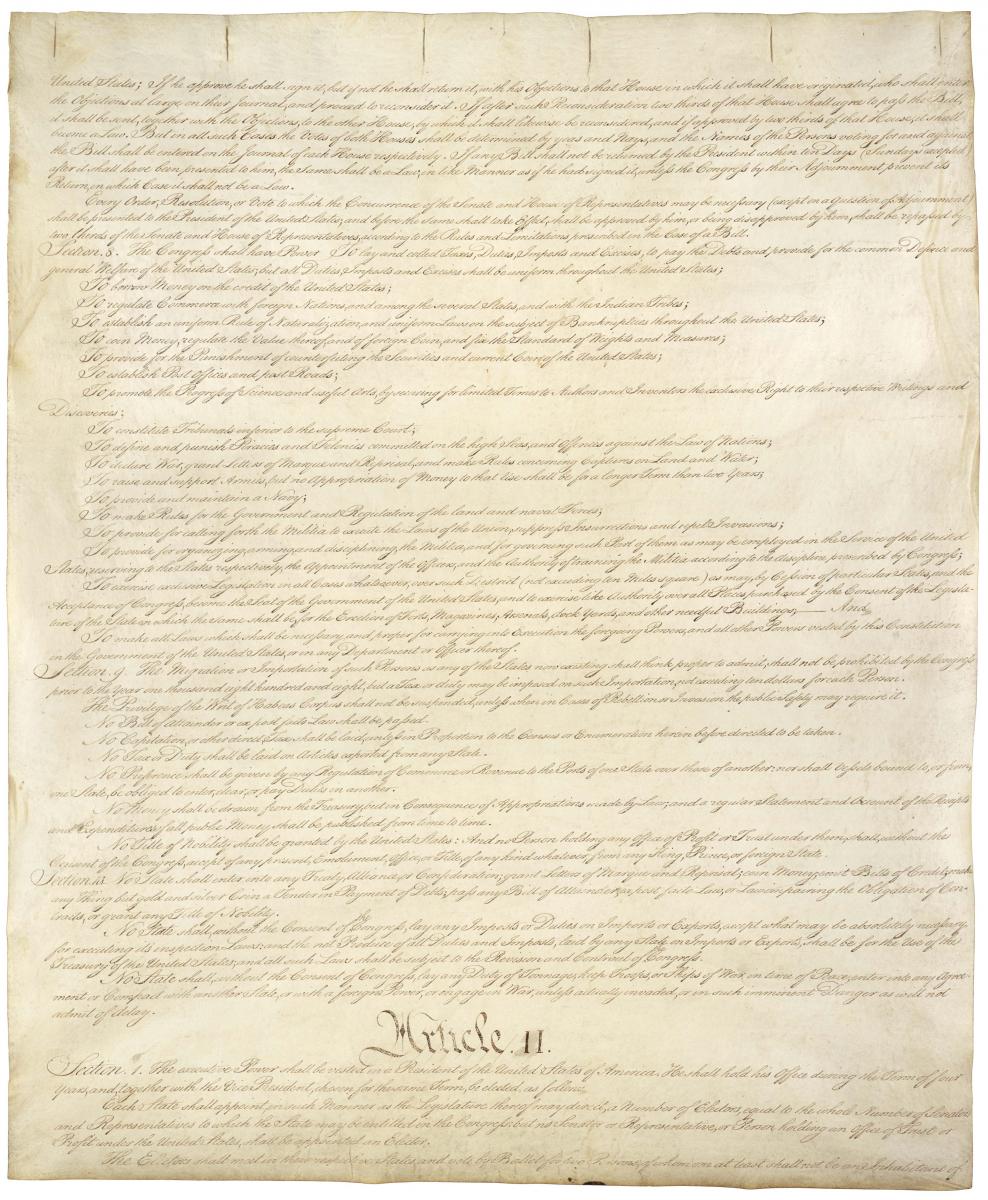

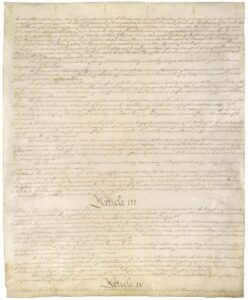

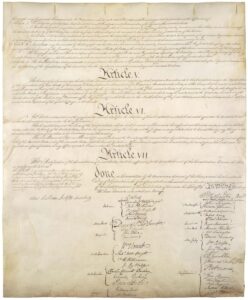

The U.S. Constitution defines the framework of the Federal Government, superseding the Articles of Confederation, which were deemed insufficient for governing the new nation. It begins with “We the People,” establishing a federal system with separation of powers—legislative, executive, and judicial—and is the world’s longest surviving written charter.

What It Is: It seems likely it’s the supreme law of the land, outlining the powers and limitations of the government, reflecting its adaptability through amendments.

When Written: Drafted during the Constitutional Convention from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in the summer of 1787.

Why Written: To create a stronger central government capable of handling issues like interstate commerce, taxation, and defense, addressing the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation.

When Approved: Signed by the delegates on September 17, 1787, and ratified by the states from December 1787 to June 1788, with the ninth state, New Hampshire, ratifying on June 21, 1788, making it official. It went into operation on March 4, 1789.

Author: Delegates selected by the state legislatures from 12 of the 13 original states, with Rhode Island refusing to send delegates. James Madison, often called the “Father of the Constitution,” was a key figure.

Where Written: Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the same location as the Declaration’s adoption.

When Signed: The delegates at the Constitutional Convention signed it on September 17, 1787.

Where Now: Also at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom.

An unexpected detail is its longevity as the world’s longest surviving written charter, reflecting its adaptability through amendments, which continues to guide the nation today.

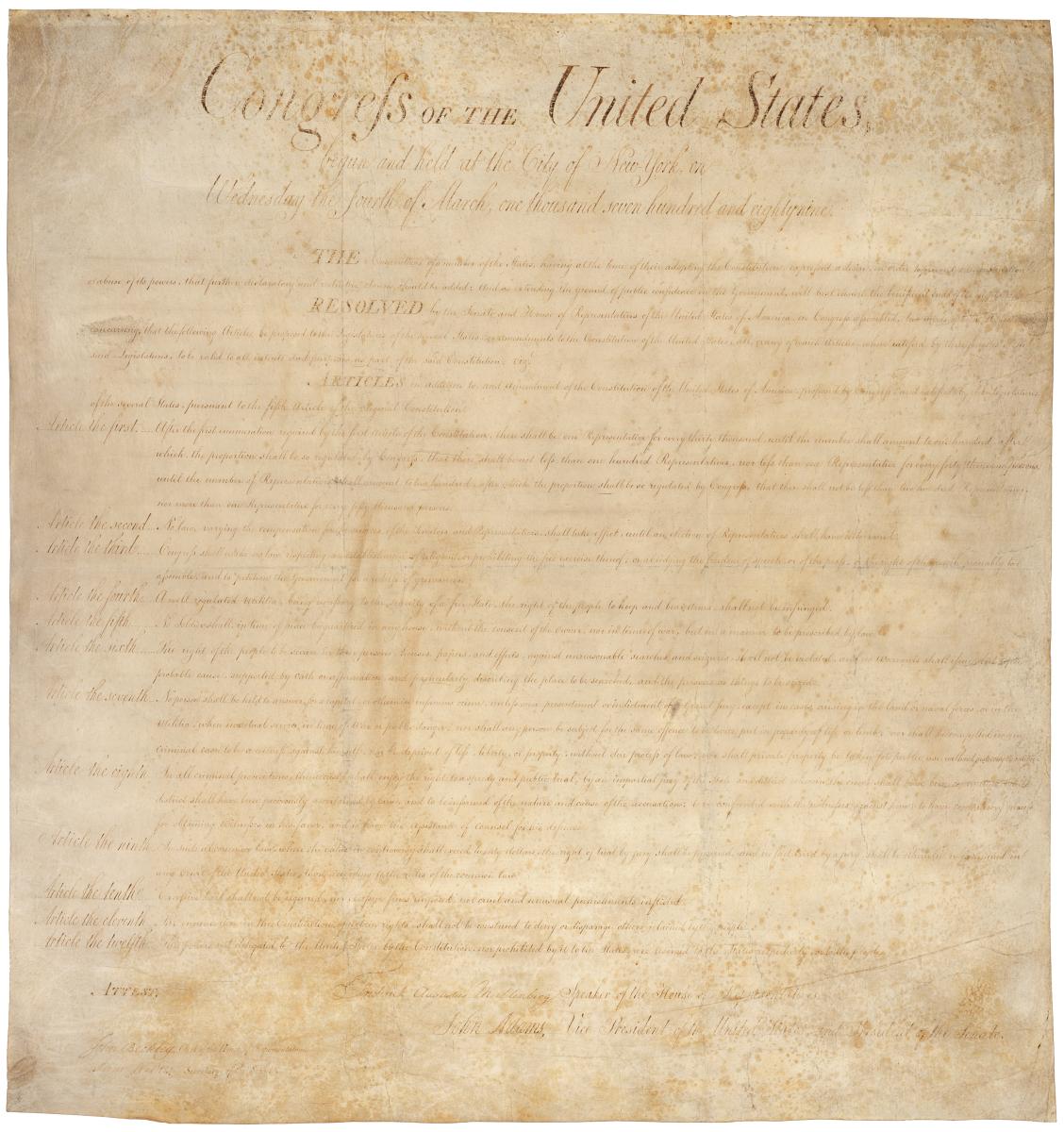

Bill of Rights: Safeguarding Individual Liberties

The Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution, spells out Americans’ rights in relation to their government. It includes freedoms like religion, speech, and the press, the right to bear arms, protections against unreasonable searches, and more, ensuring the federal government only has powers explicitly spelled out, with others reserved for the states.

What It Is: The evidence leans toward it being crucial for protecting individual rights, addressing concerns during the Constitution’s ratification, known as the Massachusetts Compromise.

When Written: Adopted and proposed by Congress in 1789, with James Madison drafting the initial versions, known as the “Father of the Constitution.”

Why Written: It was a condition of ratification of the Constitution, to address concerns that the original document did not sufficiently protect individual rights, ensuring broader support for ratification.

When Approved: Ratified on December 15, 1791, when Virginia, the 11th state, completed the process, making it part of the Constitution.

Author: James Madison, although proposed by Congress, reflecting a collective legislative effort.

Where Written: The Bill of Rights was proposed by Congress meeting at Federal Hall in New York City in 1789, where the new government convened.

When Signed: The enrolled copy was signed by the President of the Senate (John Adams) and the Speaker of the House (Frederick Muhlenberg) on September 25, 1789, before being sent to the states for ratification. Note that, unlike the Declaration and Constitution, it wasn’t signed by delegates in a signing ceremony but by Congressional leaders as part of the legislative process.

Where Now: The original copies are at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom, alongside the other charters.

An unexpected detail is that, unlike the other documents, it was signed by Congressional leaders, highlighting its legislative origin rather than a convention of delegates, reflecting its role as amendments.

Comparative Analysis and Modern Relevance

These documents, created between 1776 and 1791, form the backbone of American democracy. The Declaration set the ideological stage, the Constitution provided the structural framework, and the Bill of Rights ensured individual protections. As we approach 2026, their legacy is evident in American values of liberty, equality, and self-governance, influencing global democracy promotion.

For instance, the Declaration’s principles inspired civil rights movements, while the Constitution’s adaptability through amendments, like the 19th Amendment for women’s suffrage, shows its living nature. The Bill of Rights remains central to debates on privacy, free speech, and gun rights, reflecting ongoing challenges in balancing individual and collective freedoms.

To engage with this history, freedom250.net offers keepsakes like wood golf tees, white golf balls, and coffee mugs, each bearing the Freedom250 logo, symbolizing pride and connection across generations. These items, available for purchase, provide tangible ways to honor the 250th anniversary, connecting past struggles to present celebrations.

Summary of Key Details

To encapsulate the essential details, here’s a quick reference table summarizing the key aspects of these foundational documents:

| Document | What Is It | When Written | Why Written | When Approved | Author | Where Written | When Signed | Where Now |

| Declaration of Independence | Declares independence from Great Britain, outlines founding principles | June-July 1776 | Justify break with Britain, seek foreign support | July 4, 1776 | Thomas Jefferson, Committee of Five | 700 Market St, Philadelphia, PA | August 2, 1776 | National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| U.S. Constitution | Defines federal government framework, supersedes Articles of Confederations | Summer 1787 | Create stronger central government | Ratified 1788, effective March 4, 1789 | Delegates from 12 states | Independence Hall, Philadelphia, PA | September 17, 1787 | National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| Bill of Rights | First ten amendments, protects individual rights like free speech, religion | 1789 | Address concerns, ensure Constitution ratification | December 15, 1791 | James Madison, proposed by Congress | Federal Hall, New York City | September 25, 1789 | National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

This table provides a concise overview, perfect for quick reference or to share with friends and family as we all look forward to 2026.

Reflections and Modern Relevance

As we reflect on 250 years of American freedom, these documents remind us of the ideals that continue to guide our nation. Their creation, from Philadelphia’s historic halls to New York’s Federal Hall, underscores the collaborative effort to build a democracy. freedom250.net/shop celebrates this with keepsakes that honor our shared history, connecting generations through the enduring flame of patriotism.